Made by @Guest

Table of contents:

Introduction

Terminology

1 FLIGHT BASICS

1.1 Taxi

1.2 Take-off

1.3 Flight

1.4 Landing

2 COMBAT BASICS

2.1 Weapons categorization

2.2 Combat HUD

2.3 Sensor display

2.4 Radar

2.5 Guidance systems usage

2.6 Commonly used munitions

2.7 Surface-to-air threats

3 COORDINATION

3.1 Terminology

3.2 Strike mission procedure

3.3 Airspace authority

3.4 Runway designation

3.5 NATO brevity codes

4 ADVANCED FLIGHT

4.1 Advanced landing

4.2 Emergency landing

4.3 Stalling

4.4 NoE flight

5 ADVANCED COMBAT

5.1 Air-to-ground combat

5.1.1 Loadout

5.1.2 Holding / Engaging

5.1.3 GPS/INS-guided strikes

5.1.4 Two-seater jets

5.2 Air-to-air combat

5.2.1 Loadout

5.2.2 Holding

5.2.3 Engaging

5.3 Missile evasion

5.4 Stealth

Footnotes

Introduction

This guide is meant to teach interested players how to fly, and how to do it competently. I will be going over many things you'll likely find useful, from the basics to big booms to not becoming a big boom.

This was designed for flight in Arma and on our servers, and may not apply to other servers. It definitely does not apply to other games, and much of what is mentioned would be ridiculous in real life or simulators.

While you may find short lists here, this is not a catalogue of munitions or planes. There are other guides for that.

This is not everything there is to know about flying and planes. I can't put every possible thing into the guide, no matter how basic, and there are many features I didn't bother including that you will learn from testing and experience.

Before starting, make sure you have a large view distance. Around 8000 is usually the default for jet pilots.

Let's begin.

Terminology

The guide will repeatedly make references to various factors, control surfaces, devices and indicators present on and affecting your plane. This section is a glossary for some of those terms. If you're completely new to this, I suggest having another tab open on this section so that you don't have to keep scrolling all the way up to find a term.

Axes of rotation

Attitude: the orientation of your plane relative to its velocity.

Pitch: the vertical angle at which the nose of your plane is pointed.

Roll: the angle at which your plane is rotated around the axis connecting its nose to its tail.

Yaw: the angle in which your plane is pointed relative to its velocity along the horizontal plane.

AoA: "Ange of Attack", your pitch relative to your velocity.

Forces

Thrust: the force of your engine pushing you forward.

Lift: the force of the air under your wings, pushing your plane upwards.

Drag: the force of air resistance on your plane, slowing it down.

Control surfaces

Elevators: the two panels on the sides of your tail. These move up and down, and control your pitch.

Ailerons: panels near the ends of your wings. These move up and down in opposite directions to each other and control your roll.

Rudder: the vertical panel on the back of your tail. This moves horizontally and controls your yaw.

Flaps: panels usually on the rear edge of your wing. These extend back and downwards, controlling both lift and drag.

Airbrake: large panels on the wings or hull of your plane. These extend vertically to increase drag and slow you down. Not to be confused with spoilers.

Altitude

ASL: altitude "Above Sea Level", i.e. your vertical displacement from the sea. MSL: "Mean Sea Level", basically the same thing for our purposes.

ATL: altitude "Above Terrain Level", i.e. your vertical displacement from the ground directly beneath you. Also known as AGL: "Above Ground Level".

Aircraft designation

Fighter: an aircraft designed primarily to engage enemy aircraft.

Attack: an aircraft designed primarily to engage surface targets.

Bomber: an aircraft designed primarily for dropping bombs. (This differs from attack aircraft in that attack aircraft are supposed to be capable of using various types of ordnance such as missiles and cannons).

Weapons

Launch platform: the carrier of the device from which a rocket or missile is launched. E.g.: a plane, helicopter, infantry-portable rocket-launcher, etc.

Hardpoint: a point on the wing or hull where a weapon can be attached.

Fire-and-forget: descriptive of a weapon that will continue tracking its target autonomously regardless of whether the launch platform is doing so.

Lock: a state in which a weapon has recognized and is tracking a target.

FCS: "Fire Control System", a computer-controlled system of components working to guide a weapon accurately onto its target.

Countermeasure: anything used to misdirect or disrupt a guided weapon.

PIP: "Predicted Impact Point", the expected location of impact of a released ordnance.

CCIP: "Constantly Computed Impact Point", a PIP calculation updated at a high frequency taking into account various factors such as weapon type, pitch, range, velocity, etc.

Airfields

Runway: a strip of land designated for taking off and landing.

Taxiway: a strip of land designated for taxiing.

Exit: a short taxiway used to enter or exit a runway, usually connecting in from the side.

Miscellaneous

Landing gear: whatever you use to land. In most planes, these would be the wheels.

Wheel-brakes: the brakes on you wheels.

HUD: "Heads-Up Display", the green holographic display in front of the pilot; present in most jets.

HMD: "Head-Mounted Display", a HUD built into the pilot's helmet.

Stall: a state in which an aircraft falls out of the air, with little to no control, as a result of extremely low velocity.

FLIGHT BASICS

TAXI

Taxiing is when you "drive" the plane along the ground.

Keep the speed low (below 50 as a general rule of thumb).

You can use Q and E (by default) to turn. Make sure you take it even slower at the turns: some planes have very wide turning circles, and some simply flip over if you make a tight turn over at 30km/h.

Keep it smooth. Most paved airfields have continuous yellow lines marked on the taxiways for guidance.

Your GPS screen and/or map will help if you aren't familiar with the layout of the airfield. Keep in mind that some runways don't have exits at their far ends; if you travel too far after landing, you may get stuck or be forced to use the dirt to get back to a taxiway.

TAKE-OFF

You would normally want to get your plane into the sky in order to fly. This is very simple to do.

After taxiing to the base of the runway, be sure that the following factors hold true:

Flaps are fully extended. The flaps increase the amount of lift generated by the air moving under your wings. The further extended they are, the lower your minimum take-off speed will be - hence the shorter the distance of runway you need to accelerate and take off.

You are properly aligned to the runway. It will be difficult to take off if you run into a tree at 200km/h. Make sure that you are pointed directly at the far end of the runway, even if your plane isn't exactly centered.

You are ready to take off. Once you have clearance:

Increase your thrust. In most planes, you can safely just stick it up to 100%. You can use a lower setting, but it will take longer for you to achieve sufficient lift.

User your rudder. If your plane begins to lose alignment fro the runway, use Q and E to keep it centered. Small movements.

Pull up. Once you reach take-off speed (150 - 300 km/h depending on the plane), you can use your elevators to increase your pitch.

Keep in mind that if you go too fast without pulling up, your plane might lift off the runway and smack back down into it.

Congratulations, you're in the air.

Raise your landing gear. It creates unnecessary drag.

Raise your flaps. The faster you go, the more lift is generated under your wings. The flaps become unnecessary once you're going fast enough, and only create drag.

There are three flap settings: retracted, half-extended, fully extended.

You can pull them back to half at around 250 - 350km/h, depending on the plane.

You can fully retract them at around 300 - 450 km/h, depending on the plane.

You don't have to retract them but, as mentioned, they create unnecessary drag and waste fuel.

Start rising to whatever altitude you've been assigned. This marks the end of the take-off phase.

FLIGHT

Speed and altitude

Your speed and altitude are visible on the top-left of your screen by default. You will also be able to see the two on the HUD, usually with the speed on the left and altitude on the right.

The altitude indicated on the top-left of your screen is ATL. That indicated on your HUD may be either ATL or ASL.

The faster you go, the less maneuverable your plane will be. You will also lose maneuverability when moving too slowly, due to the reduced airflow over your wings.

The slower you go, the less lift you are generating. Extend your flaps if you want to move slowly without losing altitude.

You will lose maneuverability at extremely high altitudes as the air becomes thinner. This isn't an issue in the altitude range at which we normally operate (< 5000).

The HUD

The HUD shows you a variety of statistics about your plane and its environment.

We've already gone over speed and altitude. Using the A-10D as an example:

On the left you can see the pitch, roll and speed. You would also see "FLAPS" had the flaps been extended, and "GEAR" had the landing gear been extended.

On the right you can see the altitude and vertical speed, indicated with arrows. Your vertical speed is the rate at which your altitude is increasing or decreasing.

The dotted line in the middle is the artificial horizon. This shows the plane's horizon. It is always perpendicular to the average force of gravity on the plane at the plane's position (i.e. it is exactly horizontal from you).

The cross in the middle of the HUD is the boresight symbol. It is static and shows you where the plane is pointed. In most cases, this looks like a "W" instead of a cross.

The circle with three lines sticking out of it is the flight path vector. Your plane usually won't go exactly where you point the boresight, so the FPV shows you where your plane is actually going. You can use the FPV to maintain altitude by aligning it to the artificial horizon.

Finally, you have the heading indicator at the bottom. This shows you where the plane is pointed in relation to the Magnetic North (i.e. your bearing).

Indicators present on the HUD and their positions vary depending on the plane.

I will delve into other parts of the HUD in other sections.

Movement

You should know the basic flight movement controls. You may want to reconfigure some of them, especially if you have a flight stick, throttle, pedals, etc. By default:

SHIFT and Z control the thrust. (Controls -> Plane Movement -> Increase Thrust / Decrease Thrust)

W and S control the elevators. (Controls -> Plane Movement -> Nose Up / Nose Down)

A and D control the ailerons. (Controls -> Plane Movement -> Bank Left / Bank Right)

Q and E control the rudder and guiding wheel. (Controls -> Plane Movement -> Left Pedal / Right Pedal)

Left CTRL + Mouse Scroll controls your flaps' positions. (Controls -> Plane Movement -> Flaps Up / Flaps Down)

X extends the airbrake. (Controls -> Plane Movement -> Speedbrake). You can also map the airbrake to an analogue device.

Use your ailerons and elevators for rapid changes in attitude.

The rudder should only be used for small attitude corrections.

Planes, especially combat jets, are designed to be able to pull up much more sharply than down. If you want to rapidly lose altitude, roll your plane upside-down.

Learn to use your rudder when turning. If you simply roll yourself sideways and use your elevators to turn, you will lose altitude as a result of your wing orientation (the wings provide most of the lift). Instead, roll your plane over partway, use your elevators to turn, and use the rudder to keep your nose from rising too far. Keep your FPV on the horizon (or a different pitch angle if you want to lose or gain altitude during the turn).

How far you roll and elevators/rudder proportion depend on how hard you're turning and how much altitude you want to lose or gain during the turn.

G-forces

G-forces are forces exerted on your body as you accelerate rapidly in a direction perpendicular to your flight path (i.e.: pitching up or down sharply). Excessive positive G-forces will cause you to "black out" as blood is pulled away from the brain. Excessive negative G-Forces will cause you to "red out" as blood is forced into the brain. You can typically endure higher positive Gs than negative, so avoid hard dives as much as possible. You can identify excess G-force by the edges of your screen turning black or red, and your field of view becoming progressively smaller until you pass out. Loss of consciousness due to G-forces only lasts a few seconds, but that can be more than enough to kill you if you're heading toward a mountain.

There are two things you need to avoid this:

Pilot status. This is an in-game parameter that indicates you are trained to stay stay conscious in such situations. You will have it by default if you slot in via RPTR, otherwise you can assign it to yourself at the statue in spawn. You don't get it if you slot in as Zeus, so keep that in mind when testing and practicing.

A G-suit. Having pilot status will be of little value without this. It applies pressure to your abdominal muscles, keeping your blood in your brain. Any of the vanilla "pilot coveralls" work.

This is usually only relevant in tight turns where you accelerate "upwards" (where the top of your head is pointed, not necessarily vertically). Accelerating downwards will cause your blood to rush to your brain and eyes, filling your vision with red. You won't pass out, so the only negative to this is that you temporarily lose the ability to see.

Stalling

Turning hard will cause you to lose a lot of speed. If you lose too much speed the airflow under your wings won't be enough to keep you in the sky, and you will stall.

There are a few ways to avoid this:

Don't turn too hard. Your direction changes at a slower rate, and you will thus have more time to accelerate during the change in direction. This, of course, is simply impractical in many situations.

Increase your thrust. Increasing thrust can, at the very least, reduce the extent to which you lose speed.

Deploy flaps. If you lose a lot of speed, deploy your flaps to increase lift.

Point your plane downwards. Allow gravity to provide some additional acceleration so you can regain speed quickly.

Stalling isn't a likely issue to occur during turns. These are more ways of dealing with loss of speed than stalls. As such, I'll be discussing how to escape a proper stall in a later section.

LANDING

(note: the airbrake and wheel-brakes use the same keybind)

Good luck rearming after you've crashed and blown yourself up on a 2-kilometer-long, flat surface.

There are two things you need to be able to do to land:

Create a balance between low speed and sufficient lift.

If you go too fast, you will damage your plane upon touchdown.

If you go too slow, you will damage your plane upon touchdown; but this time because you stalled out and hit the ground like a rock.

Predict where your plane is going.

With practice, you should be able to touch down exactly where you intend to. Until then, you'll be fine as long as you don't miss the runway.

You could use the glide slope indicator, but it's important to be able to land without instruments. As such, I'm not including it.

Here's a general procedure:

Receive landing clearance.

Draw yourself a line to the airfield on the map. This should be aligned as closely as possible and be straight for at least 3 kilometers. This part is not necessary but will definitely help when learning.

Lower your altitude. Begin to descend. The distance at which you begin descent depends on what altitude you start from and how quickly you drop it, but try to do this from far away when learning (e.g.: 3-5 kilometers).

Reduce your speed. As you approach the airfield, slowly reduce the throttle and extend the flaps. You should know by now that the flaps will slow you down, but also keep you from stalling. Extend the airbrake if necessary.

When you're about 1 kilometer away, check that:

Your landing gear is down.

Your flaps are fully extended.

We talked about the FPV in "FLIGHT". In most planes, it will show you exactly where you're going (some work a little differently, but this holds true with most planes, including all vanilla jets. The C-130, for example, is an exception).

Use it to aim for the base of the runway. You will probably need to keep your nose raised slightly due to your low velocity. If your FPV falls out of sight, you're too slow.

If you notice that you're not properly aligned as you get closer to the runway, use your ailerons to roll in the direction in which you need to adjust while pushing the rudder in the opposite direction to keep your nose pointed forwards.

500m away:

Speed between 250 and 350 km/h, depending on the plane.

Altitude below 100m.

100m away:

Maintain approach velocity.

Altitude below 50m.

At the base of the runway:

By this point, you should be less than 10 meters off the ground.

Cut your throttle and extend the airbrake. Increase pitch slightly to smoothen your descent. This is called flaring.

After your rear wheels touch, you can allow the nose wheel to drop onto the runway.

Retract flaps.

Do not stop on the runway - increase throttle slightly and keep moving until you reach an exit. If you're moving too quickly to turn into an exit, just skip it and go for the next one.

Do not commit to a landing if you're not sure you'll make it. Go around and try again.

That marks the end of "flight basics". Practice these things, especially landing. Learn from your mistakes, see where you go wrong and correct them in subsequent attempts.

COMBAT BASICS

We've reached the big boom part. Let's start with the weapon types.

WEAPONS CATEGORIZATION

Platform/target

AG: air-to-ground. Launched from your plane at a ground target.

AA: air-to-air. Launched from your plane at an airborne target.

AA can also refer to "anti-air". Which one I'm referring to will be obvious enough in context.

And, of course, you have the autocannons that can be used on both target types.

Guidance type

There's a large variety of guidance systems used by the munitions available to you:

Dumbfire: no guidance, but in many cases you can predict where they will go. Short-range, AA and/or AG.

IR tracking: locks onto infrared radiation, i.e. heat. Vehicles with running engines, IR grenades, etc. You will not be able to lock onto vehicles if their engines have been turned off long enough for them to cool down. Generally short-range, AA or AG. IIR (imaging infrared, used on most modern IR-tracking missiles) is always the best IR-tracking option.

CCD: charge-couple device, similar to IR but works on a wider band of wavelengths, including visible light. Locks on to contrasts, meaning any vehicle that doesn't look like its background, even if its engine is off. Generally short-range, AG.

TV: television. This can have different meanings: it may be a contrast seeker similar to CCD, or it may send a video feed back to the launch platform which returns a signal with corrections (e.g. remote control by a WSO). (technically CCD could do the same thing, but I haven't found any examples of this in weapons)

Semi-active laser homing: locks on to lasers. A laser designator - from your own plane, a different plane, or an infantry unit - is aimed at the target. The laser bounces of the target and into the receiver of your weapon. This means that you need to be moving in the same direction in which the laser is pointed so that it can bounce back to your plane. Medium to long range, AG.

Semi-active radar homing: radar guided. "Semi-active" indicates that it doesn't have its own radar transmitter, only a receiver. This means you need to have your own radar turned on and aimed at the target for the missile to work, with a few exceptions. Long to very long range, AA or AG.

Active radar homing: radar guided. "Active" indicates that it has its own transmitter, therefore it will track the target with its own radar after being launched. Fire-and-forget (sort of), usually long-range, AA or AG.

Passive radar homing: locks on to radar signals. Designed to home in on enemy radar systems. Long to very long range, AA or AG.

GPS/INS: uses the global positioning system, accelerometers and gyroscopes to track where it is in relation to a geographic target. Fire-and-forget, very long range given the right altitude and munitions, AG.

EO is "electro-optical", the category within which TV and CCD fall.

Munition type

Defined by whether they're guided and how they're propelled.

Round: propelled by an explosive charge. Can be inert or explode on impact. Dumbfire only, always ballistic. AG and AA. Usually present on planes in 20 or 30mm cannons.

Bomb: falls from the aircraft, no propulsion. Dumbfire, semi-active laser homing, GPS/INS, IR. AG. There are various modified variants:

- Increased drag: has tailfins intentionally designed to increase drag and reduce the horizontal distance through which the bomb travels. Generally dumbfire only.

-

Glide bomb: has wings which extend upon release, designed to greatly increase its range. All are GPS/INS-guided, some have additional sensors.

Cluster bomb: contains a dispenser that spreads many smaller bomblets over a wide area. Dumbfire or GPS/INS-guided.

You never need to be pointed directly at a target when dropping a bomb unless you are intentionally dive-bombing it.

Rocket: flies out ahead of the aircraft under its own propulsion. Dumbfire only. Usually AG.

Missile: a guided rocket. Can use all available guidance systems. AG or AA.

(rockets and missiles aren't necessarily defined by guidance and are somewhat interchangeable, but I'm defining them this way for ease of explanations)

Effective range

This defines the distance from which you can reliably hit and damage a target with a given weapon.

"Short", "medium" and "long" area all comparative words, and so are not universally constant. As such, the only way one can properly use these categories is to define them. For this guide, they are defined as follows:

Short: AG < 1km, AA 1 - 5km

Medium: AG 1 - 5km, AA 5-10km

Long: AG 5 - 10km, AA 10 - 20km

Very long: AG > 10km, AA > 20km

Again, these ranges are for Arma and have been made for the purposes of fixed-wing aircraft in our modpack. In reality, 10km would be considered medium-range at most for a fixed-wing aircraft.

Similarly, any other distances I mention in this guide are specific only to our servers.

Warhead type

You should know which weapons are best suited against specific targets. There are way too many warhead types to go over, many of them extremely niche. This is a general list.

You should already be aware of these from playing as infantry.

Anti-infantry / light vehicle

HE: high-explosive. Can also be used against buildings and heavily armored vehicles when employed in large quantities, such as in bomb fillings.

HE-FRAG: high-explosive fragmentation, just HE with shrapnel.

Thermobaric: usually a fuel-air mixture, designed to make large fireballs.

Anti-armor

HEAT: high-explosive, anti-tank. Designed to explode, creating superheated strands of metal under high pressure and momentum to tear through armor.

Tandem HEAT: HEAT with an additional stage meant to penetrate reactive armor (those big blocky plates on tanks such as TUSK Abrams variants).

AP: armor-piercing. Doesn't necessarily explode, usually uses materials designed to penetrate armor. Not to be confused with "anti-personnel" unless referring to a mine.

FAT: flechette anti-tank. Releases multiple sharp, dart-like projectiles designed to rip through armor.

Anti-air

I'm not going to go over these as the variation doesn't make a difference with our modset. Most of them are designed to blow up near an aircraft, make lots of holes in it.

WEAPONS HUD

Before going over how to effectively use each weapon system, I'll describe a few aspects of the HUD relevant to killing things.

The dot in the center of the large circle is the pipper, meaning "PIP marker" where PIP stands for "Predicted Impact Point". The pipper shows you where your ballistic munitions will hit.

The number beneath the pipper is the time to target; indicating, in seconds, for how long the munition will travel before impact.

On the bottom-left is the selected weapon. Quite simply, it shows the name of the weapon you currently have selected.

The green blips on the HUD show identified targets. In many planes, these will show up as green squares. These are just vehicles the jets sees and will show up regardless of whether they are friendly, hostile, civilian or empty.

The white square shows your selected target. This is technically not part of the HUD, but is used as if it were.

The broken circle to the right of the pipper is the targeting camera position. It shows you where the targeting camera is pointed. This is useful when you've found a target via the camera, but it is too far away to see with the naked eye.

The display on the right side of the screen is the sensor display. White squares are visible on it, showing the target positions in horizontal relation to the plane. I'll go over this in the next section.

The white square with the edges of a diamond around it indicates that you are locking on to the selected target. The edges will move inwards until they form a diamond with a white dot in the middle. This means the weapon is locked on and ready to fire.

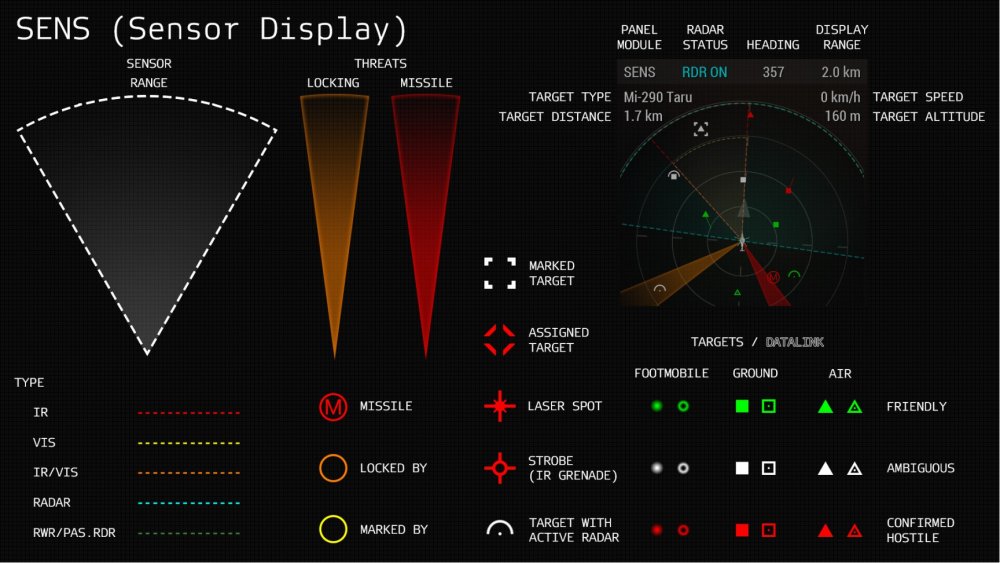

SENSOR DISPLAY

Abbreviated to "SENS", the sensor display shows targets, friendlies, threats and marks in horizontal relation to your position. [(left or right) square bracket] toggles the display when you are in a vehicle with sensors.

Look at the example display in the top-right of the image.

Squares are ground targets.

Triangles are airborne targets.

Green is friendly, white is unknown/civilian/empty, red is hostile. Keep in mind that most hostile targets will show up as white unless the mission is scripted to make them red.

The red square has a small line extending from it. This indicates its direction of travel.

A semi-circle around a target indicates that it is using active radar.

The orange sector indicates that a target with an active radar is locking on to you.

The red sector indicates that a missile is engaging you. You can see the missile, marked with a red "M".

Your selected target is marked with a white square.

You can see on the top that the radar is on.

Next to that, you have your heading.

All the way in the top-right, you have the range shown on the display. This can be adjusted using CTRL + [square bracket].

On the top-left it shows the name and distance from you of the selected target.

On the top-right it shows the speed and altitude of the selected target.

The arrow directly ahead of the helicopter symbols shows the Magnetic North.

You'll find out more about certain sensors in other sections.

RADAR

In aircraft with active radars, the top of the SENS will show the radar status. "RDR ON" indicates that your radar is set to active, when it is both transmitting and receiving radar signals. "RDR OFF" indicates that your radar is set to passive only, when it is only receiving radar signals.

Some aircraft, such as the MiG-29, don't show a sensor display panel. Instead, the radar status will be indicated by "рл" on the HUD if it is turned on.

Your radar needs to be turned on to see the speed and altitude of a selected target.

The passive-only mode can be used for stealth, as well as finding and targeting active hostile radars.

USAGE OF GUIDANCE SYSTEMS

How to use the guidance systems to lock and destroy targets.

I will not go into details about approach specifics; that will be dealt with in advanced combat.

Note: instead of using the "lock" key (T by default) to lock onto targets, you will - in many cases, if not all - find it more convenient to use the "next target" keybind (R by default). This allows you to select targets without needing to center your view on them, will only select targets that can be hit with the weapon you have selected at the time, and will not select friendlies (you may sometimes want to select friendlies intentionally using the lock key though, for example if you are escorting them and need to keep track of where they are). It will also allow you to cycle through various targets without needing to adjust your view.

Dumbfire

Visually acquire your target.

Align your pipper to the target. If the plane doesn't have a pipper, you may need to fire a test shot to see where it hits so you can adjust accordingly. Don't do this with bombs.

Engage.

IR tracking / CCD

Visually acquire your target.

Lock on to the target.

Engage.

Usually fire-and-forget, so feel free to wave off afterwards.

Laser-guided

Before starting off with this: for ACE, and BAF AGM-114s, ACE AGM-65s and ACE Kh-25MLs your laser code needs to match that of the laser designator if you aren't self-designating. CTRL + ALT + Q will increase it, CTRL + ALT + E will decrease it. Default code is the minimum: 1111.

Acquire the laser. The laser bounces off the target and back towards your plane, so you will need to be pointing in the direction the laser is. If the FAC is pointing the designator at a target to his south-west, you will need to be moving from the north-east to the south-west.

If you are self-lasing, you will have to:

- Point the targeting camera at the target. If you have one, the default keybind to open it is CTRL + RMB. The crosshair must be on the target.

- Stabilize the targeting camera. This will fix its position on the target. Default keybind is CTRL + T.

- Activate your laser designator. Switch to the laser designator and press the fire button.

Lock on to the target. Your plane doesn't need to be pointed directly at it, though you should be moving in its general direction. For GBUs, you don't need to wait for the locking diamond to close. In the case of ACE/BAF AGM-114 variants, the ACE AGM-65L, and the ACE Kh-25ML, the laser symbol next to the code - on the top-right of your screen - will turn red to indicate a lock. (Note that many GBUs LOAL, which means you won't be able to lock on beforehand. Just keep the laser on and maneuver into a position from where they can reach the target when you drop them)

Engage. Keep your laser on the target until impact. If the lase comes from another source, you can fire and forget.

Semi-active radar homing

Point your radar at your target. This can just be in the general direction of the target.

Lock on to the target.

Engage. As the missile does not have its own radar transmitter, you will have to keep yours pointed at the target until impact.

Active radar homing

Point your radar at the target. Even though the missile has its own radar, it uses yours to find the target before release.

Lock on to the target.

Engage. These are fire-and-forget, but do not wave off immediately if using these missiles against other fighters as they are likely to evade them.

GPS/INS

Acquire a geographic location. This can be a map marker or a grid-reference, usually relayed to you by the FAC.

Set the GPS target coordinates. Open the I-TGT system via the action menu. Click DGN, then click on the location of the target on the I-TGT map interface. Click SEL to assign that target to your FCS.

Get into position. You need to be moving in the direction of the target at a distance, velocity and altitude such that the munition is able to reach the target.

Engage. You don't need to lock on. As long as release factors are suitable, the munition will automatically go for the I-TGT target marker location.

After the weapon impacts, you can open the I-TGT interface again and click CLR to unassign the target, then DEL to delete the target marker.

We will delve deeper into more advanced aspects of GPS/INS guidance later, where I will explain procedures that will allow you to do things such as hit and destroy a moving vehicle from 20km away without ever knowing its exact position.

COMMONLY USED MUNITIONS

A short list of the munitions you're most likely to use as a beginner pilot.

Keep in mind that this is not a full list. The fact that something is on the list doesn't mean that you should have it by default, and the fact that something is not on the list doesn't mean it isn't useful. These are just the simplest munitions that are commonly used and easy for beginners to work with.

Main cannon

20, 25 and 30mm cannons: most common round types are HE and AP (and variants of each such as HEI, API, HEISAP, HE-FRAG, etc.), usually come in mixtures such as combat mix (API 4:1 HEI)

Examples include the GAU-8 (A-10, 30mm), GAU-12 (AV-8B, 25mm), M61 (F/A-18, F-22, 20mm), and GSh-30 (everything Russian, 30mm).

Rockets

Hydra: one or three pods per hardpoint, 7 rockets per pod (though some planes can take 12-rocket pods). HE and AP warheads available, as well as other variants such as incendiary. Close to medium range.

S-8: one pod per hardpoint, 20 rockets per pod. HEAT, tandem HEAT, thermobaric. Close-range.

S-5: one pod per hardpoint, 16 or 32 rockets per pod. HE, HE-FRAG, HEAT, HEAT/FRAG. Close-range.

Missiles

AGM-65 Maverick: up to three missiles per hardpoint. AT, other penetrating warheads, not designed for infantry targets. Guidance can be EO / IR / laser depending on variant. Medium or long range depending on variant.

AGM-114 Hellfire: one, three or four missiles per hardpoint. AT, anti-bunker, thermobaric depending on variant. Active radar / laser depending on variant. Medium to long range. Active radar homing variants are not available for fixed-wing aircraft.

Kh-25: one missile per hardpoint. AG. IR, laser, TV, anti-radiation. Medium-range.

AIM-120 AMRAAM: one or two missiles per hardpoint. "Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile". Active radar homing. Long-range, has a minimum range of about 750m. Base-game AMRAAM has LOAL capability.

AIM-9X Sidewinder: up to two missiles per hardpoint. AA. IIR. Short-range. Very maneuverable, high off-boresight capability.

R-77: one missile per hardpoint. AA. Active radar homing. Long-range. Base-game R-77 has LOAL capability.

R-73: one missile per hardpoint. AA. IR tracking. Short-range.

Bombs

Mk-81/82/83/84: General-purpose bombs. Number per hardpoint depends on bomb weight. HE. Dumbfire. Short-range. Can be fitted with tailfins to increase drag, in which case they're called "Snake-eyes".

Bomb weight (pounds): Mk-81 - 250 / Mk-82 - 500 / Mk-83 - 1000 / Mk-84 - 2000. Higher weight means bigger boom.

GBU-12/24: Mk-80 series fitted with laser guidance kits. Medium range. GBU-12 - 500lb / GBU-24 - 2000lb.

EGBU-12/24: Mk-80 series fitted with GPS/INS and laser guidance kits.

GBU-31/32/38 JDAM: "Joint Direct Attack Munition". Mk-80 series fitted with GPS/INS guidance kits. Medium range. GBU-31 - 2000lb / GBU-32 - 1000lb / GBU-38 - 500lb.

GBU-54/56 LJDAM: "Laser JDAM", JDAMs fitted with laser guidance kits. Medium range. GBU-54 - 500lb / GBU-56 - 2000lb.

FAB-100/250/500: General-purpose bombs. One per hardpoint. HE. Dumbfire. Short-range. Number indicates bomb weight in kilograms.

KAB-250/500: One per hardpoint. HE, though there is a cluster variant. Laser, TV. Number indicates bomb weight in kilograms.

SURFACE-TO-AIR THREATS

A short catalogue of anti-air threats you're likely to come across. I'll explain how to avoid them later.

All threats mentioned have 360° rotation and high elevation angles.

Note: engagement ranges indicated are not necessarily accurate, nor are they the maximum possible ranges. They are the average maximum ranges at which the AI was found to launch weapons.

Engagement ranges can be drastically extended via data links.

I'm categorizing these as follows:

Ballistic: not guided after launch. Also known as anti-air artillery (AAA).

Precision-guided: guided after launch.

Each of the above categories is further broken down into:

Static: cannot be moved quickly.

Mobile: can be moved quickly, usually under its own power. Further categorized into:

- Armored

- Unarmored

- MANPADS (Man-portable air-defense system)

Static

ZU-23-2: Ballistic. 23mm HE rounds. Very high rate of fire. 2 crew, exposed. Has an active radar transceiver.

Praetorian 1C: Ballistic. 20mm HE rounds. Very high rate of fire. Unmanned. Has an active radar transceiver.

9K38 (Djigit): Precision-guided (IR). Very low rate of fire. 1 crew, exposed. Essentially two 9K38 Iglas strapped to a tripod.

FIM-92F (DMS): Precision-guided (IR). Very low rate of fire. 1 crew, exposed. Essentially two FIM-92 Stingers strapped to a tripod.

Mk-49 Spartan: Precision-guided (IR). 21 missiles. Medium rate of fire. Unmanned. 3.5km maximum engagement range.

Mk-21 Centurion: Precision-guided (ARH). 8 missiles. Low rate of fire. Unmanned. Has an active radar transceiver. 5km maximum engagement range.

MIM-145 Defender: Precision-guided (ARH). 4 missiles. Very low rate of fire. Unmanned. No radar transmitter, designed to be used in conjunction with radar systems via a data-link.

S-750 Rhea: Precision-guided (ARH). 4 missiles. Very low rate of fire. Unmanned. No radar transmitter, designed to be used in conjunction with radar systems via a data-link.

Note that the MIM-145 and S-750 are capable of launching missiles without locking on first. The fact that their radar may have been destroyed doesn't mean they can't still smack you in LOAL mode.

Mobile

ZU-23-2 (truck-mounted): Ballistic. Unarmored. 23mm HE rounds. Very high rate of fire. 3 crew, gunners exposed. Has an active radar transceiver.

ZSU-23-4V: Ballistic. Armored. 23mm HE rounds. Extremely high rate of fire. 3 crew, protected. Has an active radar transceiver.

Barderlas: Ballistic / precision-guided (IR). Armored. 35mm HE rounds / 8 missiles. High rate of fire. 3 crew, protected. Has an active radar transceiver. Has airburst rounds in addition to the regular ones. 3.5km maximum engagement range.

ZSU-35 Tigris: Ballistic / precision-guided (IR). Armored. 35mm HE rounds / 8 missiles. High rate of fire. 3 crew, protected. Has an active radar transceiver. Has airburst rounds in addition to the regular ones. 3.5km maximum engagement range.

AWC 302 Nyx (AA): Precision-guided (IR). Armored. 8 missiles. Medium rate of fire. 2 crew, protected. 5km maximum engagement range.

9K38 Igla: Precision-guided (IR). MANPADS. Very low rate of fire.

FIM-92 Stinger: Precision-guided (IR). MANPADS. Very low rate of fire.

Titan MRPL: Precision-guided (IR). MANPADS. Very low rate of fire.

FGM-148 Javelin: Precision-guided (IR). MANPADS. Very low rate of fire.

This marks the end of combat basics. This is by no means everything you need to know. In the advanced combat section, we will go over such things as combat flight, self-defense, stealth, inter-aircraft cooperation, and more.

COORDINATION

This is where I teach you how to coordinate and communicate with your FAC, as well as other aircraft in the AO (to some extent).

This part is important. Be sure to get it down fluently.

This section is essentially the FAC guide cut down and modified for fixed-wing pilots.

Feel free to read the actual FAC guide to get some insight on what's going through the FAC's head.

https://www.fuckknows.eu/guides/arma-guides/command/fac-guide-r15/

Your long-range frequency should be set to 68. You will use this to talk to FAC and aircraft which are too far to reach on the short-range. I suggest having a long-range radio with you that you wear on you chest when you're in a plane with a parachute on your back. This will be useful in case you need to contact somebody for a rescue after you've ejected.

Your short-range frequency should be set to 180 to talk to other aircraft in the AO. If there are 4 or more active aircraft that have been split into teams, you may be assigned a specific frequency for your team between 180 and 189.9. In this case, you would just use your long-range to contact the other team (and Flight Lead if they're on a different short-range).

TERMINOLOGY

The terminology that you will need to know for effective communications.

Game-plan terms

Control type: The type of strike being ordered, categorized into 3 types that differentiate in what measures the FAC takes to make sure you don't hit friendlies.

- Type 1: the FAC will visually acquire the target and attack aircraft during the terminal phase of the attack, prior to weapons release, while maintaining control of individual attacks.

- Type 2: the FAC will utilize other measures to mitigate risk of friendly fire while maintaining control of individual attacks. (FAC won't see the target, but still take measures to make sure you don't hit friendlies)

- Type 3: The FAC will utilize other measures to mitigate risk of friendly fire while permitting multiple attacks in one engagement. (type 2 but you'll be allowed multiple strikes in one strike mission)

Method of attack: whether or not you are to acquire a visual on the target to engage.

- Bomb on target: you're required to see the target to engage.

- Bomb on coordinate: you're expected to hit a geographic location, defined by a map marker or grid-reference.

Ordnance / desired effect: the FAC will tell you if they want you to use a specific munition / the FAC will tell you exactly what they want to happen to the target.

Six-line terms

Ingress: an IP ("Ingress Point", a named map marker that you must pass on your way toward the target) or cardinal direction from which you should approach the target.

Target type: what you're attacking.

Target location: where the target is. Usually a map marker or grid-reference, though it may be a named town or landmark.

Mark type: how the target is marked. This could be colored smoke, a laser designator, an IR grenade, or nothing.

Nearest friendlies: where the nearest friendly units are, usually in relation to the target.

Egress: the cardinal direction in which you should leave the target area.

Other terms

AO: Area of Operations.

Racetrack: a path followed by a jet while awaiting tasking. Can be used for surveillance.

Orbit: a round racetrack around an AO.

Floor: the lowest altitude at which you are allowed to fly.

Roof: the highest altitude at which you are allowed to fly.

Contour flight: flying at such an altitude that you may have to adjust your path to avoid hills, usually below 300m.

NoE flight: "Nap of the Earth", flying as close to the ground as possible, usually below 50m in jets.

STRIKE MISSION PROCEDURE

Here's the order of communications from the beginning to the end of a strike mission:

Game plan -> 6-line -> Engagement.

Have a pen and paper with your, or some other way to take notes quickly.

Game plan

There are three parts:

- Control type

- Method of attack

- Ordnance / effect desired

FAC: "[your callsign], FAC, advise when ready for game plan."

Tell them you're ready if you are, otherwise reply with "standby" to indicate they should wait.

FAC: "[control type], [method of attack], [ordnance / effect desired]. Advise when ready for six-line."

Finish taking notes and report in when you're ready for the six-line.

Six-line

I'll leave you to guess for yourself how many parts there are.

- Ingress

- Target type

- Target location

- Mark type

- Nearest friendlies

- Egress

After the sixth line, the FAC may also mention additional remarks such as AA presence.

Readback of lines 2, 3 and 5 is mandatory. The FAC may request a full readback.

FAC: "[line 1], [line 2], [line 3], [line 4], [line 5], [line 6]"

Read back the mandatory lines, or all if a full readback is requested. Ask them to repeat a specific line if you missed it.

FAC: "[confirms accurate / makes corrections]"

Read back the corrections if any are made.

FAC: "Report IP inbound."

Engagement

This is where you report in to FAC, get clearance to strike and leave.

Report in when you are crossing the IP.

If you don't see the target, "no joy". If you can see it and can engage, inform the FAC and request fire clearance. "Tally, confirm hot" (use "spot" instead of "tally" when targeting a laser marker).

FAC: "cleared hot / wave off".

If cleared hot, you're free to engage. Announce weapons release. If not cleared, hold fire and proceed to egress.

FAC: "[BDA]"

You must always make sure you are cleared hot before engaging unless the target poses a definite, severe and immediate threat to you or friendly units.

FK FACs currently use "eyes on" instead of "tally".

How to announce weapons release is outlined in the Brevity Codes section.

Feel free to provide a BDA to the FAC if they don't have eyes on the target.

AIRSPACE AUTHORITY

Dictates where you need permission for specific actions, and from whom to get that permission.

FAC-controlled airspace: you are not allowed to enter, land, or engage targets in the airspace without explicit permission from the FAC.

Visually controlled airspace: controlled by the first person to get eyes on the airspace, often Flight Lead. Permission is usually only needed if flying at low altitudes.

Uncontrolled airspace: if the FAC allows you a certain degree of autonomy, you can move through this airspace at your own discretion. You should still get permission to engage a target unless it poses an immediate threat to you or a friendly unit.

No-fly zones: airspace you are not allowed to enter, usually due to expected AA threat or priority to stealth.

In general, the home airbase would be visually controlled, objectives or areas with AA would be FAC controlled, and everything else is uncontrolled.

RUNWAY DESIGNATION

Runway designations have two parts: the runway heading and the side.

The runway heading is the bearing at which a plane has to fly to align itself to the runway, divided by 10 and rounded to the nearest whole number.

The side denotes which runway is referred to when there are multiple parallel runways.

For example, look at this image of the main Altis airfield (aligned so that up is north).

On the south-west ends of the runways, you can see that one is 04-L and the other is 04-R.

On the north-east ends, you can see that one is designated 22-L, and the other 22-R.

Bother runways designated 04 require a plane to be coming in at a heading of about 040 to land. When looking from that side, L is on the left and R is on the right.

Both runways designated 22 require a plane to be coming in at a heading of about 220 to land. When looking from that side, L is on the left and R is on the right.

Therefore, 04-L and 22-R are the same runway, as are 04-R and 22-L. The designations just make it easier to figure out which one is being referred to, and from which side you are expected to come in.

In airfields that have 3 parallel runways, the center one would have the letter designator "C".

An example landing clearance would sound something like this: "Raptor one one, cleared to land runway zero four left."

Many modded maps have completely random, inaccurate runway designation markings.

NATO BREVITY CODES

Various terms to concisely communicate information.

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a404426.pdf

The exact meanings are adjusted for use on our servers.

It is recommended that FACs learn these as well.

Home plate: home airfield or aircraft carrier. (we often use baseplate)

Angels: altitude in thousands of meters. (officially feet, but we use meters on our servers)

Winchester: out of ammunition.

Bingo: having barely enough fuel to safely RTB.

Joker: slightly more fuel than Bingo. The fuel state at which the aircraft should begin returning to base.

Bandit: hostile aircraft.

Bogey: unidentified aircraft.

Spike: RWR detection of hostile radar in track phase or hostile anti-air missile launch.

Buddy spike: aircraft is being spiked by a friendly.

Buddy lock: aircraft weapon is locked on to a friendly.

Faded: radar contact lost.

Low: contact is at a low altitude. (> 1000m)

Medium: contact is at a medium altitude. (1000 - 3000m)

High: contact is at a high altitude. (3000m - 5000m)

Very high: contact is at a very high altitude (> 5000m)

Slow: Target has a low estimated speed. (< 500kmh)

Fast: Target has a high estimated speed. (500 - 1000kmh)

Very fast: Target has a very high estimated speed. (> 1000kmh)

(very high isn't an official brevity code, but has been added for use on our servers) (values have been adjusted for use on our servers)

Speed check: NOT an official brevity code. Request for the current speed readout of another aircraft.

Alpha check: request for bearing and range to a described point. (e.g. "Spiked." "Alpha check." "250, 6 klicks" / "Eyes on a T-72 group." "Alpha check." "120, 5 klicks.") (you can provide altitudes as well) (values are from the describing aircraft's position)

Status: request for an aircraft's tactical situation.

Cleared hot: munitions release authorized.

Continue dry: munitions release not authorized.

Repeat: repeat fire mission using the same parameters.

Abort: cancel fire mission. (FACs on our servers often use "wave off")

Cease fire: stop firing. (any ordnance already released may continue to target)

Cease engagement: terminate the fire sequence. (any ordnance already released may continue to the target. Continue tracking the target)

Laser on: start of laser designation. FACs on our servers often use "lase on deck".

Cease laser: order to another aircraft to deactivate their laser.

Spot: laser designation is acquired by the aircraft.

Guns, guns, guns: firing main cannon.

Rifle: AG missile launch.

Bombs away: bomb release. (we often use "Pickle" on our servers)

Magnum: release of anti-radiation weapon.

Ripple: multiple ordnance releases in one strike.

Fox: air-to-air missile launch.

- Fox 1: semi-active radar-homing AA missile.

- Fox 2: IR-tracking AA missile.

- Fox 3: active radar-homing AA missile.

Maddog: ARH missile release without lock.

Splash: Weapons impact.

Grandslam: all detected hostile aircraft are neutralized.

A few common ones that are too obvious to name, such as "contact" and "friendly", have been left out.

If you are comfortable dealing with multiple frequencies at once, it can help to listen in on 69 so you can respond to infantry call-outs quickly and save time on waiting for the FAC to relay messages. Keep in mind that you still need to be told by FAC to engage if you aren't continuously weapons green; hearing the call-outs just allows you to find and lock on to the target beforehand.

That's all for communications, it's fairly straightforward. Remember that as the pilot, you ultimately make the decisions over your aircraft. If you deem entering an area to be too high-risk, you can reject an order to do so.

ADVANCED FLIGHT

Time to start getting spicy.

By this point I expect you to have sufficient practice to be capable of doing all the basics with ease.

I also expect you to be able to do simple research, as I will not longer be explaining every term that appears here.

ADVANCED LANDING

Here I'll be going over landing harder planes, and in more difficult situations.

Keep this in mind for all landing methods: if you can't see your FPV, you're going too slow.

Altitudes mentioned in this section are not ASL or ATL, but above the runway's elevation.

While most of this is explained in terms of the FPV, it translates easily into the movement of the plane itself and is almost the same without instruments.

Values used are approximate and depend heavily on the plane. Don't take them for law.

Short landing

You will be trying to touch down as close to the base of the runway as possible.

Your speeds will be extremely low.

Your plane should be under 30m when you're 100m out, moving at about 250km/h in swept-wing jets, and 180km/h or lower in straight-wing jets such as the A-10.

Keep your FPV slightly after the base of the runway.

You should be under 5m when you reach the base of the runway. Pull the air- and wheel-brakes as soon as you reach it, or a few meters before depending on your speed.

If you're not sure whether you'll be able to make it by the time you're halfway down the runway, kick the throttle to maximum and take off for another try.

If you are slowed to under 70 but still about the reach the end, turn off into a taxiway or onto the grass. You can also try zig-zagging across the runways to increase the distance you have to slow down. The latter is a little ridiculous, but sometimes works because Arma.

If the runway is on a hill, you can also try approaching from below its elevation and using the altitude increase to slow you down. You will have to know its layout beforehand as you won't be able to see it on approach.

This is dangerous. Do not try it during a mission until you've practiced and perfected it.

Carrier landing

Treat this like a short landing, but make sure your tailhook is down beforehand. You only get the option to lower the tailhook once your gear is extended. You should be landing from the back of the carrier as that's where the arresting wires are.

Keep in mind that the first few meters of the carrier runway on the USS Freedom are angled downwards. Don't hit them.

Some planes can be landed on carriers without tailhooks, such as the A-10D and L-159. (technically, even the F/A-181 can do it without a tailhook. It's just more difficult)

Damaged runways

You may have to land on a damaged runway, or one that has debris or other obstacles on it (or a platoon that's decided that the runway is a suitable waiting area).

Pick the longest clear area of the runway.

Treat it like a short landing and use your guiding wheel to avoid debris.

You do not have to land in the center of the runway, use the sides if you deem them safer.

In most cases of a damaged runway, you will find it easier to simply land on a taxiway or the dirt alongside it.

Of course, in some planes, you don't need more than a 100m of flat surface to land anyway.

EMERGENCY LANDING

There are three possible scenarios here:

1. You have a leaking fuel tank.

2. You have no fuel or your engine is inoperable.

3. Your controls surfaces are heavily damaged.

There are other scenarios as well, such as an influx of heavy AA threats or the pilot getting shot, but these only require you to get to an airfield quickly.

In case of a leaking fuel tank:

Find the nearest airfield on the map.

Judge how much time you have left before you're out of fuel.

Land at the airfield or gain sufficient altitude to be able to glide to a runway.

Once you're at a high enough altitude, you can set the engine to idle to conserve fuel and only use the throttle when necessary. You can also cut the engine, but keep in mind that it takes time to start back up in some planes.

In case of loss of thrust:

You would normally already be at least 1000m in the air. If your engine got shot out at a low altitude, pull up smoothly to gain some altitude with the speed you have.

Check the map for any nearby airfields. Judge whether you'll be able to get to them.

If you can't, take a look around and see if there are any suitable fields you can land in.

If not and you still have good altitude and speed, check the map for any suitable-looking terrain within your range.

Glide to it. Do not use your airbrake or otherwise intentionally drop speed at any point. You can reduce it during final approach.

Once you have the landing zone in sight, pick the smoothest strip of land and treat it like a short landing (don't overdo the low speed though, you don't have any thrust available to get you out of a stall).

Use the rudder and front wheel to avoid obstacles.

If you're too high and fast when you're coming up to the landing zone, pass over it and come in from the other side.

If it looks like you're going to hit something or you can't land safely, eject. Your safety has priority over the plane.

In case of severely damaged control surfaces:

A damaged control surface does not warrant an emergency landing unless there is a high risk of crashing as a result. Except for in the aforementioned case, landing with damaged control surfaces would be considered a normal landing in which you do not get priority over other traffic.

If you need to land with damaged ailerons or elevators, just counteract the force manually.

If your ailerons are damaged to the point where you cannot keep the plane horizontal, allow yourself to slowly roll over while maintaining a path to the runway. Control the rate of roll by either counteracting or moving with it in such a way that you are aligned when you touch down.

Keep in mind that your negative vertical speed when you're upside-down is much larger than when you're the right way up.

Landing on the side of a hill

Good luck trying this with swept-wing aircraft (except for the ones with ridiculous flight models).

You should always be landing uphill. Attempting to land downhill or accidentally taxiing over to the other side of a hill will result in you being unable to stop and eventually crashing.

Attempting to land perpendicular to the hill's gradient will result in you flying off sideways because of the roll required to avoid clipping the wing.

Pick a hill with a reasonable gradient, although this isn't usually a choice you have.

Pick the clearest and longest strip of hill you can find.

Fly low, with the intent of touching down at the base of your chosen strip. Your speed should be high enough that you can pull up.

When you are about to reach the base of your strip, pull up to align yourself with the hill's gradient and engage the air- and wheel-brakes.

After pulling an emergency landing on an airfield, try to use your remaining speed to pull off the runway and clear the space for other aircraft.

Some of these landings are much easier explained than done, but you should be able to do them with enough practice.

The An-2 can land almost anywhere, so that's a fun one to do it with. Not too useful for practice though. Start with easier ones with low stall speeds and short landing distances, then move on to more difficult ones that stall more easily, take longer to slow down on the ground, and are more sensitive to rough touchdowns.

Don't start with the easiest, most unrealistic planes though. I found the A-10D to be a good beginner's plane for emergency landing.

Only the F/A-18, F/A-181 and UCAV Sentinel have tailhooks.

EJECTION

If you are unable to land the plane safely, be it your control surfaces are too heavily damaged or you're out of fuel over a forested area, you always have the option to eject. At this point, your main goal is to not end up dead or in the middle of the ocean.

Look for a good location over which to eject. In order of priority, the area you eject over should:

- 1. Have little to no hostile presence. There's really no point ejecting if you're going to get shot on your way down. However, if you might find yourself deep in enemy territory, try to find a vehicle. If you can't fight your way out, simply surrender. Gives the infantry another objective, as well as someone to laugh at.

- 2. Be within comms range. In some planes, whatever backpack you have automatically gets replaced by a parachute upon ejection, so you won't have a long-range. Switch your short-range to whatever frequency the nearest element uses and explain your situation.

- 3. Be friendly-accessible. This can be at your airbase, next to friendly squads, somewhere the transport chopper can land without getting blown up, etc.

After ejecting, scan the area and find a suitable point to touch down. You should also try to go for somewhere you can actually leave after landing, i.e. avoid roofs, deep pits, compounds from which the exits are blocked by hostiles, etc.

After landing, mark your position on the map and contact friendlies to arrange for extraction. Think about what vehicles the platoon has available to them and suggest a good pick-up point, for example: a flat, open area for a helicopter or along the road for land vics. Let them know about any possible hostiles near you.

Make sure to tell FAC you're ejecting before you do so.

STALLING

You went too slow, now you're falling out of the sky. Good job.

I'm defining this section not just as losing altitude as a result of low speed, but going so slowly that you fall straight out of the sky with no control over your aircraft.

Getting out of this is quite easy. Maximize throttle, fully extend flaps, and do your best to point your nose at the ground. You're looking to gain enough speed to regain control, but not so much that you won't be able to pull up in time. Once you have control, pull up in a smooth arc.

Don't pull up as soon as you can though, give it a bit more speed after you have control. Otherwise, you risk entering another stall as a result of the drop in speed due to the change in direction. The only exception here is if you're really close to the ground and have no choice.

As soon as you've pulled up, you may still be losing altitude. Activate afterburners.

Only retract your flaps once you've stopped losing altitude and are back at a safe velocity.

NOE FLIGHT

A mobile sonic boom blasting past a meter overhead makes for a good show.

More importantly, NoE flight can be used to avoid guided AA emplacements and escape enemy fighters.

All altitudes mentioned in this section are ATL unless otherwise specified.

There are various forms of NoE flight in fixed-wing aircraft, namely:

High-speed NoE.

Medium-speed NoE.

Low-speed NoE.

High-speed NoE

Sustained speed over 1000km/h.

Your altitude will generally fluctuate between 0 and about 200m as the terrain beneath you rapidly changes.

Don't try to duck into valleys as you won't be able to pull out of them.

Use your FPV to fly close to hilltops, between tall structures and under power lines.

Good for evading enemy fighters on your tail.

Medium-speed NoE

Between 500 and 800km/h. 350-500 should be considered medium-low and 800 to 1000 medium-high.

Smaller altitude fluctuations as you'll be able to follow the terrain more closely, between 0 and 100m.

Good for CAS strikes when there are light AA threats (.50 cals, autocannons not designed primarily for air targets) in the target area and guided AA threats in other parts of the AO.

Low-speed NoE

Sustained speed under 350km/h, flaps fully extended and nose raised. You'll be on the brink of stalling the entire time.

With practice, you'll be able to keep your plane at around 10m throughout the flight, and lower if there are no trees. Over airfields and other flat areas, you'll be able to maintain 1m given good control over your plane.

Use your FPV to avoid hitting the ground.

Good for avoiding detection by specific radars (I'll explain later) and decapitating infantry with your wings.

This is the only way light AA can reasonably be expected to kill you, and MANPADS will definitely take you down. Only do this in appropriate situations.

You'll often find yourself switching between medium- and low-speed NoE.

Play around with this. Learn your stall speeds, get familiar with the maneuverabilities and dimensions of different aircraft and you'll eventually be able to blast through such ridiculously small spaces that you need to turn your plane sideways to fit.

ADVANCED COMBAT

Anybody can drop a GBU on an armored vehicle. However, in a mission that fully takes into account the capabilities of fixed-wing aircraft, players who only know how to make tanks go boom are next to useless.

AIR-TO-GROUND COMBAT

This section will make the biggest difference in your effectiveness during most missions.

LOADOUT

General types

Air-To-Ground loadouts are somewhat difficult to categorize as they will often be mixed during missions and we have a wide range of different types of air-to-ground munitions. Because of this, I'm just listing the basic characteristics of a few for specific roles.

CAS: Most commonly used. Combinations vary greatly. You'll likely have a mixture of bombs, missiles and/or rockets in larger amounts than for other roles.

Strike: Loadouts with few but specific weapons, usually used if you have predefined targets to hit. 2000lb bombs, cluster munitions, cruise-missiles, anti-runway bombs, etc.

SEAD: Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses. You'll likely be grabbing anti-radiation missiles such as the AGM-88, Kh-25MP, and Kh-58 as well as other long-range munitions.

As mentioned before, these are just a few with general characteristics and you may take loadouts that have nothing to do with these for purposes such as laying down carpets of mines or illuminating night missions.

Fuel

You may often find yourself having to choose between a fuel tank or ordnance for a particular pylon. Your decision should depend on:

- The size of the fuel tanks. It may be a waste to replace a rack of bombs with a tiny fuel tank.

- The number of times you are allowed to refuel. This is usually infinite, but some missions restrict it to a certain number of RRR sessions.

- How long it takes to refuel. The longer you're out, the longer you're useless.

- Whether it is safe for you to land. For example, if you're likely to be attacked at home plate while on the ground. You would be practically defenseless in this case.

- How much risk you put friendlies at by leaving the AO. For example, if you're responsible for protecting friendlies from QRFs.

- How much ordnance you expect to use. The more targets you expect to hit, the more important it is to have a lot of ammunition.

- Which ordnance is being replaced. Instead of replacing the only pylon that takes important munitions, you might instead put a fuel tank on a hardpoint where that ordnance isn't available anyway.

Countermeasure pods

Some aircraft can take countermeasure pods on certain pylons. Again, you may need to decide whether you should take the pod or something else on a pylon.

As with the fuel tanks, this depends on the situation. You might be more likely to take it if you expect enemy fighters to show up, or are performing strikes in SAM-prone areas.

Some planes have internal ECM systems that allow you to perform jamming without using up pylons. However, the internal system might not be as powerful as other options, and both have advantages over each other.

I'll explain further later.

HOLDING / ENGAGING

Your hold patterns will vary depending on your role.

When providing CAS:

You could be told to loiter close to the AO to look for and destroy threats to friendly units, usually holding at about 2000m to keep a good view over the battlefield but still be able to hit targets quickly;

or be set on a racetrack further from the AO and only called in when the FAC has a specific target for you, often above 2000 meters and close to home plate.

When running strikes:

You may be set on a racetrack far from the AO and told to engage with GPS-guided munitions, in which case you'll likely be over 3000 meters in altitude;

or you might only know the target area, in which case you'll be sent to the region or set on a racetrack near it to find and destroy the targets, after which you'll likely be called back to another hold patter to switch to a different role.

In some cases, you'll be on a racetrack far away and allowed to break off for a single pass over the target and return to the racetrack.

When performing SEAD:

You'll likely be set on a racetrack far from the AO, but close enough that you can find the target using your sensors, after which you'll break off to engage it and return to the racetrack.

In many of these cases, you'll scout first and engage later; either by continuously circling the AO and engaging individual targets after reporting them in (mostly for CAS), or breaking off the racetrack for scouting runs and running strikes once you and the FAC have a good overall image of the target area (mostly for strike and SEAD roles).

GPS/INS-GUIDED STRIKES

How to take full advantage of the I-TGT system.

Multiple targets

After designating a target, you can use the arrows next to the SLOT button on the top-left to switch your selected slot. Once you have a different slot selected, you can use the DGN function again to designate another target. Once you have multiple targets, you can switch between them using the SLOT button and use the SEL function to assign a target once you have the correct slot selected.

Bomb-on-coordinate

I've already gone over the most basic way to hit a point on the map using this system. However, this can also be done by entering the 8- or 10-digit grid reference into the interface to avoid wasting time finding the coordinates on the map.

Click on the DGT button to switch between 8 and 10 digits.

Input the target coordinates, with the correct number of digits, into the text-box just above the DGT button.

Voila, the FCS will set a target marker at your selected coordinates.

On some maps, this messes up and the FCS puts the target marker at the wrong y-coordinate. In this case: input the coordinates again, but this time replacing the correct y-coordinate with the one the FCS decided to go for. This should result in the marker moving to the right place. (it seems that the FCS is designed for maps whose y-axes increase upwards, but the y-axis increases downwards on some CUP maps, so the coordinates become inverted)

Dual mode

The "mode" button on the bottom-left of the I-TGT interface cycles your guidance mode between GPS and DUAL.

Dual mode works with GPS-guided munitions that have other sensors such as IR or laser receivers. When using this mode, the ordnance will target the GPS coordinate until it identifies a target (IR signature or laser marker), at which point it will change course to hit it. If it doesn't spot anything, it will hit the GPS coordinate.

This is especially useful when you have the general location of a target but not the exact location.

For example, there's an active BMP in a town and the FAC can't mark it on the map because it's moving about. The area is protected by AA emplacements, so you can't go over and find it yourself.

Simply target the town itself with a GBU-53 and allow the bomb to find the BMP on approach.

Make sure to put the GPS marker further than the target's location so that the munition can spot the target before it reaches the marker. The marker coordinate should also be in an area where the ordnance won't hit any friendlies if it doesn't find a target.

When using dual mode with IR, make sure there are no warm friendly vehicles along the munition's flight route (the bomb won't target infantry, so they're fine). Keep in mind that vehicles take time to cool down after they've turned their engines off.

Be mindful of the target's environment. Approach in such a way that the ordnance has a good chance of finding the target in time to adjust course.

For example, if the target is in Ovallestán, in the valley between two mountain ranges on Clafghan, it's more reliable to release the munition parallel to the valley instead of perpendicular to it. In the latter case, the munition won't see the target until is passes over the mountains, at which point it may be too close to maneuver to the target.

If the munition identifies a target and changes course, the FCS will say "DUAL MODE ACTIVATED" in text chat in the vehicle channel.

Long-range GPS/INS-guided munitions

Glide-bombs

GBU-39 SDB: 200lb warhead, range over 15km.

GBU-53 SDB II: a GBU-39 with terminal active-radar homing, semi-active laser homing, and IR-tracking sensors in addition to the GPS/INS. The terminal-phase sensor when using dual mode is IR only in our modpack.

AGM-154A JSOW: "Joint Standoff Weapon", not actually a missile as it isn't self-propelled. Cluster bomb. Shaped charge, fragmenting and incendiary; so pretty much general-purpose. (look up BLU-97/B for specifics)

AGM-154A-1 JSOW: uses a different warhead (BLU-111) designed specifically for enhanced penetration. Intentionally less useful against infantry, but will slaughter any armored vehicles within its area of effect.

KGGB: similar to the GBU-39, but requires the PDU for designation.

AGM-84H SLAM-ER: low-altitude cruise missile, 500lb warhead. IR-tracking terminal-phase sensor when using dual mode in our modpack.

Some AGM-88 variants should be dual mode (GPS/INS / passive radar) in reality, but these don't seem to be the variants available in our modpack.

TWO-SEATER JETS

Some strike or multirole jets have a second seat for a weapons systems officer, whose job is to control guided air-to-ground ordnance loaded on the aircraft.

In such aircraft, the weapons systems controls are usually split between the pilot and WSO.

In general, the WSO has access to the laser designator and controls most of the guided AG ordnance, while the pilot controls dumbfire weapons and air-to-air missiles.

The WSO always has access to a targeting camera. The pilot may have one depending on the aircraft.

The pilot and WSO must constantly coordinate with each other to accurately and efficiently carry out fire missions. This is a little more complicated than in attack helicopters. While the crew chief in a gunship might tell the pilot how to adjust (rotation, altitude changes), a plane is constantly moving at a high speed and the WSO can't simply tell the pilot to "turn a little in this direction".

For this reason, the WSO must constantly communicate what they see to the pilot in order to give the pilot maximum situational awareness. This way, the WSO can simply tell the pilot what target they want to hit and with what ordnance, and the pilot can follow an appropriate approach path to get into position for the WSO to release engage. Think of it as making requests, rather than giving orders.

In order for this to work well, the pilot must have just as good an understanding of all the weapons systems as the WSO.

Just like in an attack helicopter, the pilot's biggest responsibility is keeping the aircraft safe. Of the two crew, the pilot is ultimately in charge.

More simply said:

WSO: make the big booms, keep the pilot updated as to the situation below.

Pilot: keep track of ground targets, select approach and holding patterns to the WSO's advantage, keep the aircraft safe.

Who does communications is to be decided between the two of you.

The F/A-18F and Su-34 are currently the only WSO-compatible fixed-wing aircraft in our modpack.

There are also two VTOLs with WSOs: the CSAT Y-32 Xi'an (1 pilot, 1 WSO), and the NATO V-44 X Blackfish (1 pilot, 1 copilot, 2 WSOs).

AIR-TO-AIR COMBAT

You're no longer the most powerful thing in the sky. You can and will be shot down if you get too cocky.

LOADOUT

General types

I'm categorizing AA loadouts into 3 distinct types:

- Short-range

- Long-range

- Mixed

This is pretty straightforward.

Short-range:

You'd generally take this if you don't expect to be engaging targets at long ranges at all. For example, if your targets are expected to be mostly enemy helicopters taking off from various bases and you have to fly low to avoid enemy SAMS.

Mostly short-range IR-tracking missiles such as the AIM-9X, IRIS-T and R-73. When you're close, you want highly maneuverable missiles with wide off-boresight capabilities.

Long-range:

You don't expect to be doing any dogfighting. This could be if your role for the mission is, for example, running CAP and protecting infantry by intercepting incoming enemy helicopters and CAS planes before they get close.

Long-range missiles, generally radar guided, such as the AIM-120, MBDA Meteor, and R-77.

Mixed:

This is the loadout you are likely to take in most missions. You expect a high probability of both short- and long-range engagements. This could be in a mission where you're expected to defend friendlies from incoming aircraft and there are likely to be enemy fighters coming for you.

The exact composition of your loadout depends on the mission. Naturally, you would balance out the proportion of long- and close-range missiles depending on the exact specifications of the mission.